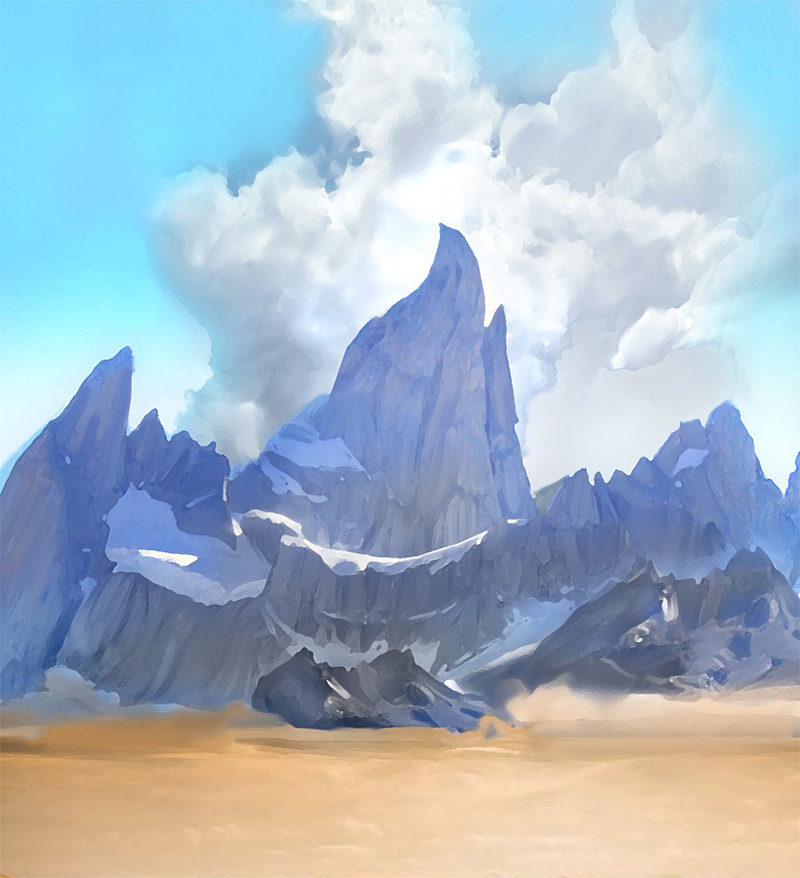

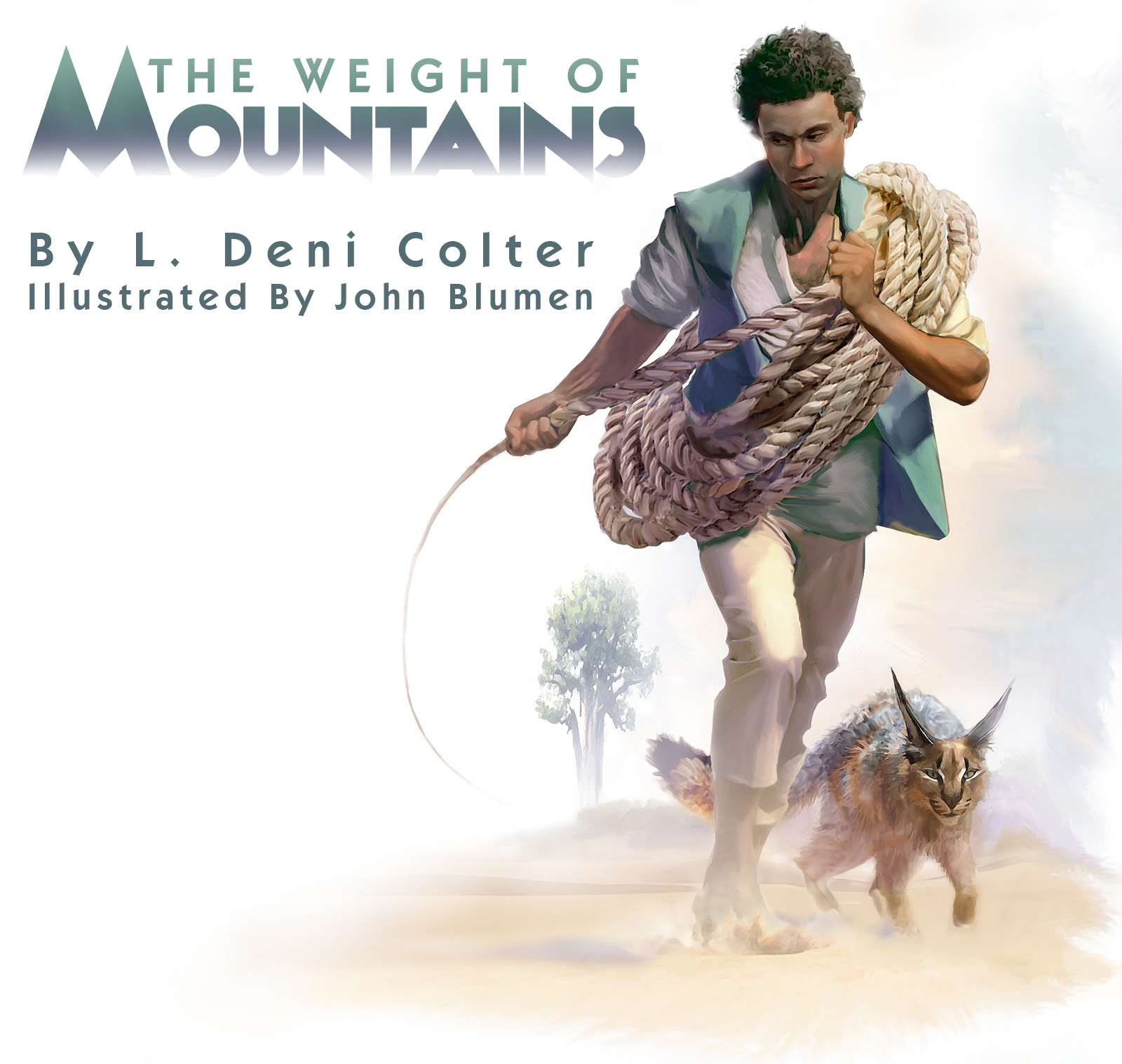

| We stopped near land’s end, Mama and I, under the branches of a tree like none I’d ever seen. It perched there at the edge of our world with roots that might go through to the other side and branches that must brush the stars above at night. Mama sat cross-legged in her canvas trousers and work shirt, same as I wore, same as most folks of our land did. The enormous coil of rope leaning against the tree had awaited me when we arrived. I stood taller and broader of shoulder than both of my older brothers who’d attempted this thing before me, and still, carrying it would be difficult, though not my greatest struggle. I wondered what doubts my brothers wrestled with when they’d stood in this place, about to begin. I picked at one end of the rope until a thread came loose. Pinching it between my fingers I pulled it free. Spun in some circular fashion, the rope would unwind bit by bit into a thread long enough to stretch to the core of the world. I circled the tree with the thread and tied it to the great trunk. "Once you pick that rope up," Mama said, "you can’t set it down again. Maybe not ever, Cinder." "I know, Mama." I sat near her, not ready to take the weight onto my shoulder yet; worried that I might never feel ready. She looked down at her ankles. Her dark hair covered half her face, light at the temples where it had turned gray after my eldest brother undertook this journey. Her bronze skin shone in the last of the daylight. "I lost them all, and for what?" "I lost them too, Mama." She looked up. "Then why won’t you change your mind?" I rested my forearms on my raised knees. "Because we were chosen for this. I owe it to our family that went before. To all the people counting on me to bind our land to the core." |

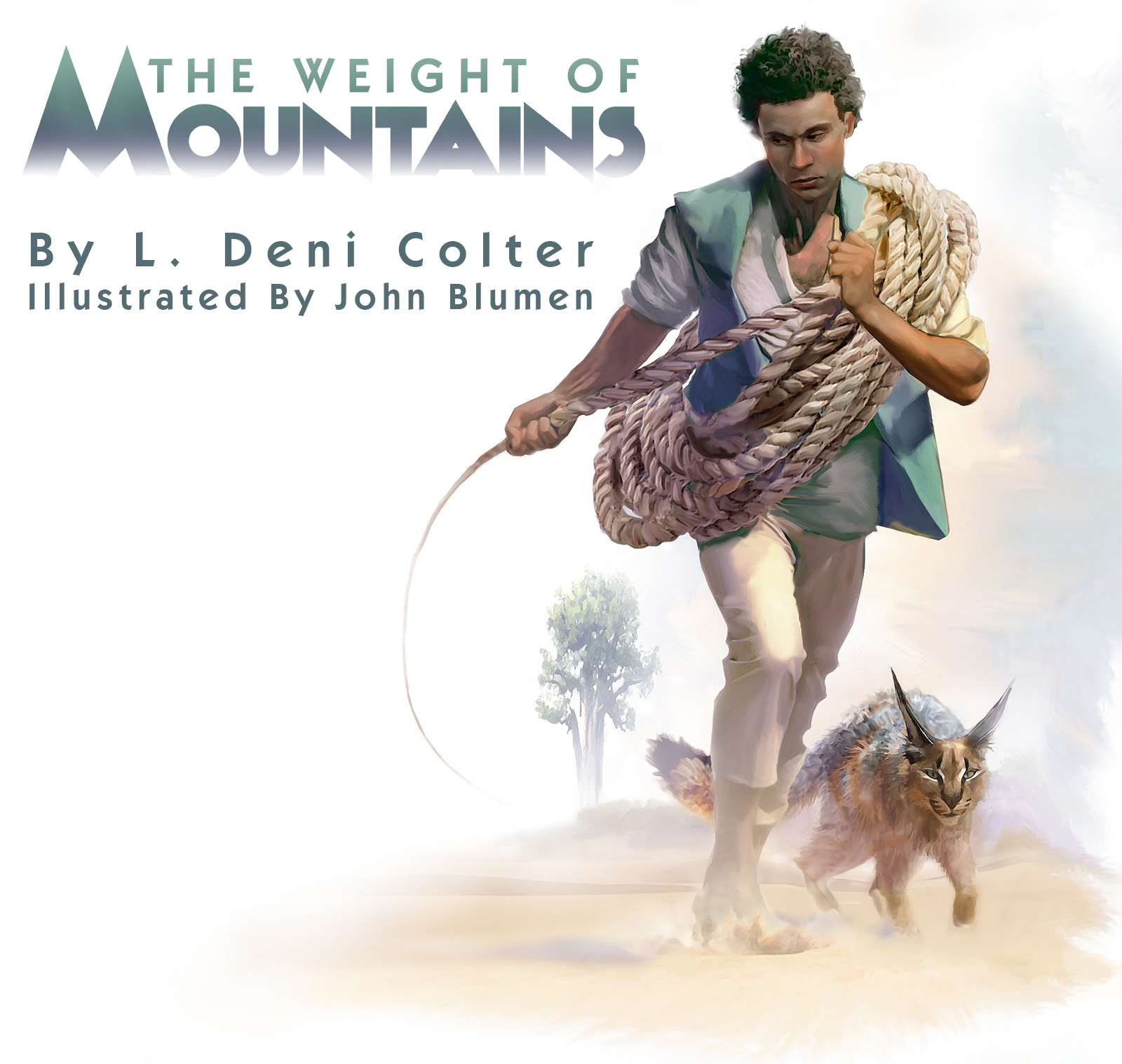

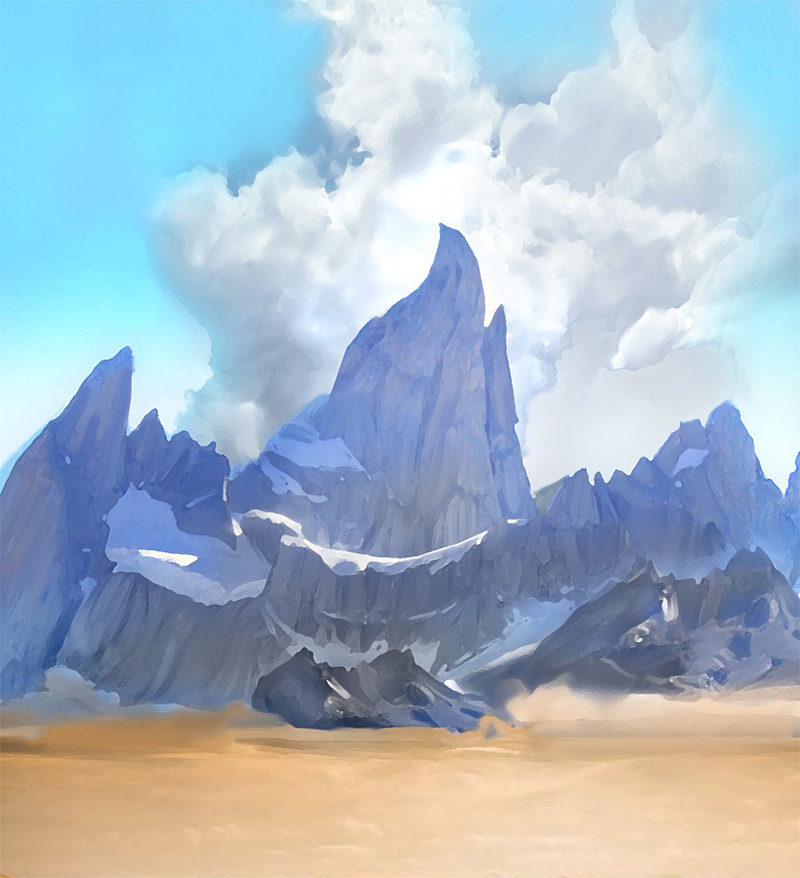

I’d spent my whole life not telling her how much I wished old man Umber had never spoken the prophecy all those years ago when he was still a young boy, foretelling that our land would break off the end of the world and float away. Naming my father’s mother as the first of our line to try and save it. My grandmother, then my father, then my two older brothers had tried and failed. "You’re young," she said. "Wait one more cycle." She looked at me with such pleading my heart ached. "I’m a man grown, Mama. Twenty cycles of seasons. I’ve had a lifetime of knowing this day might come." "Then I’m going too," she said. Her eyes held that steely look she got when determined. She’d followed me to land’s end, repeating her arguments as if I'd hear something new in them. She’d never said this before. "You can’t come, Mama. Only Daddy’s line." The boy-Umber had seen that as well. "My mother-in-binding, my palm-bound mate, and my two oldest boys all chose this over family. When you go, I’ve got no one left." "You’ve got your life." "All of you were my life." "I have to go, Mama." She made no response except to stand when I did. I bent to the enormous rope, turning away so she wouldn’t see my fear when I committed to it. My spine compressed as I hauled it onto my shoulder, my neck muscles strained. I heard her harsh exhalation, a silent sob at my back. I willed strength into my knees and started for the border. Mama matched me stride for stride. I hoped with all my heart that she bluffed; that she’d stop when we got there. One short, difficult rise later and the boundary of land’s end lay before us. It looked nothing like I’d expected. The green grass of my homeland truncated sharp as an amputated limb into the nothingness of endless yellow desert. I walked to meet it and the thread from my rope unspooled behind. Please don’t I thought as I reached the edge, but Mama didn't hesitate. I stepped into the deep, hot sand. She stepped across at my side. From one stride to the next she shrank to my knee and dropped to all fours, her clothes falling away behind. Her body sprouted thick, dark fur with buff stripes at the sides. Her head narrowed, triangular and pointed now. Her teeth and claws grew long. "Oh, Mama." It came out in a whisper, but relief that she lived overcame despair at seeing her changed to a gulo. Whatever power had changed her, I had to admire the irony that it chose a creature as stubborn, ferocious, and protective as Mama had always been. Together we passed over a border we could never cross again. I didn’t want to look back, but did anyway. Desert surrounded us; home had vanished. The only tie to it was the thread trailing across the sand. Mama already panted in the heat, the long hair on her new body warming her more quickly than me, though the desert sun overhead would wear on me soon enough. A few strides past the border, a cabin came into view. It seemed we approached it with unnatural speed. I couldn’t determine if we moved toward it or if it moved toward us. An old woman waited for us on the porch that I would have sworn empty a moment ago. She sat in a rocker of wood so weathered that all color had bled into the dry heat. Her feet were propped on a railing of branch and log, still in bark, and so derelict she might push it over with a hard shove. Smoke drifted from a pipe jutting straight out from her mouth. We halted at the porch steps. She nodded her assent and we climbed up to join her. I took a seat on a rough bench opposite her rocker, my back to the railing and the desert, my shoulder near her bare and calloused feet. Mama lay down at my side, still panting, her long teeth exposed. The creak of the rocker pumped through the still air. The woman, shriveled and yellowed as an old apricot, puffed on her pipe, the blue-gray irises of her eyes sharp in the soft decay of her face. Mama watched her, head up, alert. The old woman removed the pipe. "I welcome you to the crossing." If some traditional answer was expected, I’d never learned it and so I gave none. Perhaps this was as far as any of my family had ever made it due to nothing more than not knowing a required response. "Who have you loved most in your life?" the old woman asked without further preamble. If this proved the easiest of her questions then my test would be difficult indeed, but I knew that in this place nothing but truth would do. I looked to my mother and thought of her sacrifices. I thought of Appleonia, the maid whose love had nearly kept me from my duty when my mother’s had not. I thought of my father who’d instilled duty in me by example of his own strength and love. I thought of my older brothers. Nothing stirred in the desert around me. Each grain of sand seemed poised for my answer. I wondered if this place had looked the same to the others or different to each person who came here. "Myself," I answered. My mother turned her black, beady eyes to me in surprise. The old woman puffed a breath of smoke. "What secret did you keep from everyone you know?" Again, something easy to know, difficult to tell. "My fear." She waited for the rest. "My fear of this task. I don’t want to do this. I don’t want to be a living tether for my land, tied for all time to the core. I’m scared it’ll tear at my limbs. I worry it’ll be a torment for all eternity." I kept my arms relaxed, my feet still, but my stomach churned at the imaginings I’d harbored all my life. Mama pawed softly at my foot. At least I’d been able to keep it from her until now. The third question came while I still fought to settle my stomach from the second. "Do you believe you’ll succeed?" The easiest question by far. "No." I shook my head. "My family was stronger than I am and they failed. I don’t know why they didn’t succeed, but I suspect fear will be my undoing." A soft mewling noise came from Mama’s throat. Her hard head rubbed my calf. I was glad now that she’d been changed; gulos couldn’t weep. I could, but I blinked back the tears the admission provoked. I waited for instructions. None came. "Blessings on your undertaking," the old woman said, jamming her pipe stem in her mouth and chewing it into the right alignment. Again, I knew of no traditional response. I stood with an effort under the weight of my rope. We left the porch and the Guardian behind. The thread strung out behind me as we set out across the desert. I looked back once. A monster, large as the cabin, coiled where the cabin had stood a moment ago. It shimmered in the desert heat as if its existence were divided between this place and another. The pointed head of a viper swayed above a thick body with four taloned wings folded around long, thin legs, shiny and lithe like a widow-maker spider’s legs. I couldn't see and couldn’t guess the hind end of the creature. My rope weighed me down as much as it had since I’d first picked it up. The thread pulling from the raveled end lightened the weight so minutely, step-by-step, that I noticed no difference. The rope and the deep sand made each step an effort. Mama fared little better with her heavy coat, lifting her stubby legs high with every stride so her long nails didn't drag. "Look there," I said. I pointed and she followed my arm and finger to a hazy, purple outline at the horizon. I'd heard tales of mountains, and wondered if that might be them. If so, they were smaller than I'd been led to believe. |  |

The desert must not have been as flat as it looked, for a short while later we topped a small dune and discovered a hidden depression over the crest. At the bottom of the depression lay a man. I’d seen no sign of tracks, but perhaps shifting sand had covered them. I wondered how long he’d been here. I squatted at his back and touched his shoulder, thinking him dead until he moaned. His shoulders were as wide as my own, his upper arms and chest larger. From there he tapered to a narrow waist, as I did, but below that he shriveled to hips that could never have born weight, and legs no larger around than my forearms. Over his left shoulder was an enormous coil of rope, equaling my own. He must've crawled here from wherever he started, but it was certain he'd go no further. I pulled the flask that Mama and I shared from my pocket and offered him a drink. Mama growled, but I held it to his lips. He drank, but only a sip. The urge to take more must've been mighty, but with lindel juice a little was enough. I pulled his legs toward me and supported his back, working him into a sitting position against the dune. "I thank you for your kindness." His voice was hoarse even after the juice. "May I have your name to keep while I yet live?" "Cinder," I said. "Fulgere," he said. "You're headed for the mountains?" "I was. I got farther than I thought I would." I wondered if all from his land were physically challenged, the same as him, or if his family had been chosen despite one person’s challenges. "How many have gone before you?" he asked me. "Four from my line. I’m the youngest." He nodded, understanding all that implied. "And your companion?" "My mother." "Ah," was his only response. I offered the flask again, but he shook his head. "You'll need it more." I looked toward the distant mountains. They had grown perhaps a finger since I first saw them. Even if he abandoned his rope, he couldn't crawl home. Daddy had told us there was no going back. And in this state, he'd never make it to his goal, not even if I left him the whole flask. Mama growled, a low rumble starting deep in her chest. She’d always been able to guess what I was thinking. "We'd better get going," I said to him. "Sorry this won't be more comfortable for you." I leaned my right shoulder into his midsection. The weight of my rope nearly unbalanced me when my hands sank into the soft sand. Mama nipped at my fingers. "You can't," he protested. "You'll only die too." "Your rope will slide down once I lift you. You'll have to hold it with your hands. Can you do it?" "Yes." He didn't have a chance to say more as I pushed my shoulder into him. His broad torso fell across my back. I straightened, still on my knees, balancing his weight with the weight of my rope. That was only the half of it, I knew. His rope still rested on the ground. Mama growled again, a long, angry rumbling. There was no way to use my hands to push to my feet without my rope slipping from my shoulder. I braced one hand on the coil and one on his deformed hips, dragging my left knee up until my foot was under me. My weight, the weight of my rope, the weight of the man and his rope—my thigh took it all. Or so I thought until I looked down and saw Mama on her hind legs at my side, pushing up on Fulgere’s rope with all her muscular animal strength. My thigh shook and strained as I lifted high enough to get my right foot flat on the ground. If something in my leg tore, we were all lost. If I fell, I didn’t know if I'd have it in me to start over. I stood. My feet sunk to the ankles in the sand. Mama's bushy tail lashed in anger. I took a step, then another. "What were your siblings’ names?" Fulgere’s voice drifted up from the area of my low back. Breathless. It must've been hard for him to talk in that position. I was breathless too, but the little air I spent on words made no difference; the distraction did—as he must've known it would. "Clay was oldest." The words came haltingly, every few steps when I paused for breath. "Mama went through," a few steps more, "about a dozen...other names first... When she reached that one...Daddy agreed." Slowly we left the dune behind as I told our history. I kept my eyes fixed on the mountains as I told him that Coal was next. That was okay by Daddy too, but she had to change the spelling from C-o-l-e to C-o-a-l. My name was all Daddy, though he more often called me "Little Bit." Little bit of trouble, little bit of sunshine, little bit of mischief." Those few sentences took me more than a hundred strides. Sweat dripped from my face and ran down my back. I looked up and the mountains were half again as high, as if they rushed to meet us like the cabin had done. I wondered how far I’d actually walked. The hot desert turned cool and blue. I glanced up at the sun. It stood directly overhead still, but it receded from us, as if it flew up and away from this mid-world. "Fulgere," I panted, "day’s ending and I have to rest. Can you drop your rope and still hold one end?" Daddy had told me I must never put my rope down once I’d picked it up. Hopefully this would count close enough for Fulgere, as I couldn’t kneel under the full weight with my strained thigh. Without question he did as I asked. Mama skittered to the side as it fell with a thump. Muscles in my back that had been in spasm from the first step, lengthened. The compression on my spine lightened and my left thigh ached a little less. I dropped to my knees, bent forward, and eased Fulgere to the sand. Falling next to him, I rolled to my back, my rope still on my shoulder. Mama licked my face. I opened my eyes feeling certain I hadn't slept, yet it was full dark. Mama lay curled against my free shoulder with her nose tucked her beneath her tail. Fulgere snored lightly on my other side. I closed my eyes. |  |

|

I sat with my back to the great tree, my rope at my feet. Mama was her old self. I was dreaming, and yet I knew I wasn’t. "Why, Cinder?" she said. "If you were afraid of this all along why didn’t you stay with me? Bind your palm to Appleonia and live out your days?" I gave her the only answer I had. "I had to try." "Then why help Fulgere? It’ll kill you both before you ever reach the mountains." She shook her head in frustration. "Your logic is as full of holes as your name." I gave a small shrug. It felt good not to have the weight of the rope on my shoulder. "Why bind ourselves to the core and join other lands if all we care about is ourselves?" "Why, indeed?" she said with a bite to her words. "Many of us argued against it." "Some did," I corrected with a smile. "We might have been fine breaking off. Maybe it’s joining the core that will be our undoing, tying ourselves to lands with strange ways." I shrugged again. "Maybe, but not according to Umber. We’ve had two generations since that first prophesy to see all his others come true. The lands beyond ours that didn’t tie on broke off one by one. Nothing left anymore between us and the void. And now the earthquakes have started." I leaned my head back against the bark of the great tree. "He also said the lands that drifted away would shrivel and die." "He said so, but we have no way to know for sure." I tipped my head and met her eyes. "Do you really disbelieve, Mama?" I’d never thought she did. I always thought it was just that losing her family one by one was more hurtful to her than losing the whole world. She didn’t reply. She planted her hand in the grass and clenched at the soil beneath, as if she still had the long nails of a gulo. I woke in the morning to the sun overhead approaching incrementally, like a burning hand reaching down toward me. My muscles felt stiff, my skin cool everywhere except where my mother lay against my shoulder. I looked to my other side and Fulgere was gone. There were no hand prints or drag marks in the sand. His rope was nowhere to be seen. The thread of my own rope remained unchanged, trailing back the way we’d come. I took a quick sip from the flask and handed it to Mama. She held it for herself as she drank, sitting on her haunches and gripping it between the pads of her paws. We walked on until the thud-hiss of trudging through sand filled my world. My left thigh burned like fire with every step, my rope dragged at my left shoulder and never seemed to lighten. Mama panted and sometimes took a drunkard's weaving step. I finally took another drink from the flask, but Mama refused. In what might've been afternoon there, partway between us and the mountains that now seemed as tall as my head, another figure shuffled. Even with the distance, I guessed their stature small, bowed under the weight of their rope. Their greater struggle slowed them, and Mama and I soon came even. The other person’s path had angled away to my left, where before they had looked to be straight ahead of us. The person stopped on seeing us. We halted as well. I could see now it was a woman. She looked older than me, perhaps in her prime or a little past. Her hair, orange as an attastick flower, had frazzled, despite the braid holding the rest. Framed against the sky, it formed a hazy nimbus around her head. "Do you seek to reach the mountains?" she shouted. "I do," I called back. "You had best come this way then," she said. She panted her words, much as I had yesterday under the weight of Fulgere and the two ropes. "Straight to the center peak is the way I was taught," I replied. Mama bumped my calf. I looked down but she was staring straight ahead, as if to tell me to mind my own business. "No," the woman shouted. "If you approach the goddess to her face, it's an act of hubris. You'll be struck down for it." Umber had told my daddy’s mama that we had to pass the Guardian and survive the journey. There had been no talk of a deity. He’d seen no more, but said if one lived to reach the mountains they would see then how to tether our land. "Perhaps we’re both right," I said, thinking that maybe each land had a different protocol to follow. I looked down at Mama. She stared somewhere off to our right now; ignoring me, I suspected, for continuing the discourse. "There is one way only," the woman said, sounding more exhausted with each exchange. "Learn it or die." As with the Guardian’s questions, I looked for my own truth and found it. "I need to follow my heart. My heart believes what my father told us, that the direct path offers the surest chance of success. If you wish to travel with us, I’ll do what I can to help you." Mama rumbled, though it was soft and resigned. "Your father was wrong," the woman replied without hesitation. "You must approach from the side or you will die." "Have your people tried before?" If they had tried and failed, I had had no reason to believe her. "I’m the first," she said. She looked ready to fall where she stood. I scanned the expanse of the mountain range, the untold days extra she would need to reach the left-most point, where the peaks dwindled to low foothills. "I’ll follow my heart," I said again, "as you must. I hope we’re both right and that I'll see you at the mountains." "What you'll see is that I spoke the truth," she said. "You'll wish you'd listened." With that, she trudged onward and leftward. Her arguments seemed to have drained her. She stumbled twice before I looked away. That night, as I dreamed, I asked Mama what she thought. "Are they real, the people we're seeing?" "I don’t know," she said. She lay back on one elbow under the tree. Her hair hung loose, brushing the grass. "I know no more about this place than you do." "I’m not sure about Fulgere," I said, "but the woman felt real." I wondered if anyone had encountered my family out here; had seen them vanish when they failed some oblique test. I’d always thought myself the weakest. Full of holes, as Mama said. I’d thought it a flaw that I didn’t have the stubbornness and independence of the rest of the family, or most of the folks I knew. As strong as they were, though, it hadn’t been enough. "Don’t worry, Cinder," she said, as if her thoughts ran along similar lines. "All you can do is your best. Your daddy gave the three of you the best chance he could, in case he failed." Her face tightened at his memory, even all these years later. "He said Clay could be both hard and soft, malleable and unyielding. Coal was strong and could withstand pressure. Cinder, he said, was porous. It could both withstand and absorb. A rock that could float." "I'm sorry you came with me," I said. "But I'm glad for your company." She reached out and touched my forearm. It felt real. I woke the next morning and sensed two bodies near me. Mama lay near my shoulder again, her thick fur tickling my neck. Looking to my right a man slept on his side, facing away from me. The arm not against the ground rested atop his coiled rope, the other pillowed his head. Each breath cost him effort against the weight of the rope on his ribs. Mama’s beady black eyes widened when I sat up and she saw him. She must have been as surprised as I that she hadn't heard his coming. Our stirring woke the man. Like my own effort a moment before, he struggled to sit, but managed to keep his rope centered on his shoulder. The skin below his light purple eyes were limned with black shadows of exhaustion. "I'd hoped to pass you as you slept." He spoke with the rough voice of one who had been deeply asleep. "It seems my feet wouldn't take me one step farther." "If you prefer solitude to company we'll be on our way soon, friend." He studied me as if I mocked him. His face relaxed only a little when he saw I didn't. "I nearly drove myself into the ground trying to pass you yesterday. I prefer solitude, yes, you could say that. Because I plan to be in front." He rocked onto his knees and pushed to his feet. "You'd do best not to hinder me." He wore a yellow tunic nearly to his knees over a long brown skirt. As he tried to rise, he stumbled forward stepping onto the hem of the skirt and nearly tripping. I reached out and grabbed his hand. My purpose was to steady him, but stopping his momentum helped pull me to my feet on my sore thigh. I grabbed him by both shoulders until he was stable. "I'll not hinder you, friend," I said, "but no reason we can't work together, seeing as we have a common goal." "Isn't there now?" He pulled away from me. "So you can get in the lead, you mean? We both know there’s only room for so many." He adjusted the rope on his shoulder and winced as it dragged back to center. "Me and mine aren't going to miss out so that you and yours can have a spot." He trudged forward, his steps heavy. I didn't know how well he'd moved before, but I guessed the extra effort of catching up to us had cost him. I’d never heard of any limit, but if there was no more room when I got there then I would fail. I doubted things would end that easy for me. I pulled the flask from my pocket, watching his thread spool out behind him as he weaved away from us. Mama nipped at my calf, but she couldn’t make me hurry to catch him, and there was no point in her going faster than me. The flask felt light and I handed it to Mama before drinking myself. I could tell she took next to nothing, but when I tipped it to my lips there were only drops left. I sucked every one and tossed the empty flask to the sand. We started ahead, Mama and me, side by side. The fellow’s thread disappeared over another of the short dunes that contoured the deceptively flat expanse. When we reached the crest of the dune, I could see he’d vanished; so had his footprints and his thread. Looking back to check, I saw my own thread and my deep prints shadowed by Mama’s smaller ones near them. They stretched back until the heat haze erased them. That night we were both silent a long while, absorbing the peace of the great tree over our heads. "Are you still afraid?" she asked. "More than ever." "I'd hoped when we came here I could talk you out of this. That maybe we could live our lives out here if not at home. But I see now it isn't a real land, just an in-between place. I don't think either of us would live a single day if you stopped." She looked away, toward the border we’d irrevocably crossed. "I wish I could take this burden from you, but I don't know how." "It's mine to bear, Mama." I only hoped I could.  | I woke to the mountains right in front of us, as if they’d marched up on us in the night. They rose out of the ground, rock and earth of weight and substance beyond anything I'd ever imagined. Solid, like nothing I'd ever seen. Their weight would've punched a hole in our land and fallen right through the other side. I stood easily and stared in amazement at my rope. The coil on my shoulder was maybe a quarter of what it had been the day before. The pressure on my bruised shoulder felt like a feather in comparison. I saw no sign of my earlier companions. No one standing before the mountains except Mama and me. Mama stood on her hind legs, her short front legs hanging down, long claws resting against her belly fur. She stared at the mountains like they might jump forward and devour us. My hands trembled as I took the coil from my shoulder. Mama and I looked at each other a long moment. The center peak came to a hook at the top. I had no doubt that was the place to tether. I found the free end of the rope and fashioned an immense loop. I wondered if any of the others in my family had come this far. I doubted it. They'd been braver than me; if they’d made it this far they would have made it the rest of the way. I tried not to imagine what it would feel like if I succeeded. What it would be like to become the rope, tied at one end to the tree and the other to the mountain. The strain of the world on my limbs. Forever. Daddy said he believed it was intent that would get the rope wherever it needed to go. The one thing I didn't have. Maybe Daddy had named me wrong, left me too full of holes. If I stood here until tomorrow, perhaps come morning I'd be gone, like the others. I wouldn't have to quit, I could just do nothing. If I didn't disappear, then without the lindel juice I'd be dead before long. So would Mama. It might not be quick, but it wouldn't be eternity either. I dropped my hands, but I didn't drop my rope. "I don’t think I can do it, Mama." I didn’t look at her as I said it. "There were too many that went before me. It made you mad, but it made me scared, more with each one." |

She stood on her hind legs and pawed softly at my thigh. Her claws caught in my pants and pricked the skin beneath. I shifted the rope to my left hand and bent to scoop her up, finding her dense body heavier than I expected. Lifting her to my face, I kissed her triangular head at the soft spot between her eyes. She licked the stubble on my cheek. I didn't know if she encouraged me onward or begged me to stop, but I couldn't ask her and she couldn’t tell. I set her down. She looked up, waiting on my decision, her whiskers vibrating. To her, I’d been more important than everyone in our land put together. I thought I was different from her, that I’d come here to do this thing for them, but perhaps I wasn’t different at all. All those people counting on me couldn’t conquer my fears; not even duty to the family that had gone before me. I looked down at Mama, prepared to confirm what we both already knew, that I wasn’t brave enough. Her eyes, black pupils in dark irises so wide that no whites showed, shone with the intensity of the words she couldn’t share. My own eyes filled with tears that she’d followed me here. She might have been able to live out her natural days at home, even when the land broke free, but here my inaction would condemn her to death. She’d been willing to sacrifice a whole world to save me, and maybe that was my answer. Maybe I didn’t need to find enough courage to save a whole world, maybe I just needed to find enough to save one. Mama couldn’t go back over the border, but if I could tether us to the core then she might be able to walk out of this middle world and into a new life. I looked up at the peak, at the hook. Moving before fear could grip me again, I twirled the lasso above my head. I'd only have one throw. Daddy told me so. Thinking of Mama, I threw with intent. My loop soared upward as if it had no weight, no drag of rope behind it. It flew like a bird, up and up and up, and we stood there watching it. It flew so high it passed from sight, but I felt it when it hooked. It pulled taut as it caught our land and anchored it. My body jerked taut with it, becoming the rope I'd carried. Without even time for a goodbye, I sprang up into the sky. No tension or strain pulled at me. I didn't feel like a tether; I felt like a ray of light. I shined all the way from the tree to the mountaintop, and everywhere in between. The joining felt like a song in my heart. I could see the other lands tied to this place. Beyond them were the ones that had tried and failed—or failed to try—drifting alone in the void. I could see Mama below me. She grew tall again. Her fur fell away to smooth, bronze skin. She must have heard my song of joy because she waved and laughed and cried. She stared at my brightness a long time. Finally, she started toward the mountains. I watched her as she progressed up and then over them, into the new lands. |

|

|