Dean and I went way back. We’d met during our undergraduate years at Charles Darwin, and we soon discovered a mutual interest in anything to do with the outdoors: mostly rock climbing, some kayaking and rafting, sometimes just heading out and living off the land for a week or two. After graduation we got some grants that enabled us to work together on various ecology projects. There aren’t any mountains in the Northern Territory, but there are plenty of escarpments. And any rockhound will tell you an overhanging cliff-face is a lot more challenging than any mountain. In those days it was pretty easy to sneak in a day of climbing along with a week of collecting tadpole specimens or measuring soil and water acidity. As for the climbing, I was never in Dean’s class. We free-climbed most mornings; then after lunch Dean would usually find some overhang: 5.7, 5.8 even 5.10’s— the higher the grade, the better. I can still see him hanging in a perfect three-points-of-contact, all pecs and abs and quads, waving with his free hand, wearing just his shorts and climbing shoes, a chalk bag swinging gently from his waist, while I watched from the ground. Yes, I knew even then that I was in love with Dean. Not only his body— with him. I’m pretty sure he knew but he never made an issue of it. It was obvious that he didn’t reciprocate my sexual feelings, although I sometimes thought he almost wished that he could. But maybe that was just my imagination. So, we remained best of mates, each enjoying our outings in our own way.

I woke up on a trolley at the Royal Darwin next morning, and spent the day being wheeled in and out of the X-ray room. It was nearly evening when the orthopedic surgeon gave me the diagnosis: fractured pelvis and a broken left ankle. The ankle would require some pins but would basically be okay. The surgeon wasn’t so sure about the pelvis. There was a “significant” fracture, he said. “Internal fixation with a plate for a few months while we see how it mends. Lots of rehab. You should be able to walk again, but there might be bit of a limp.” He looked pleased with himself. I asked about Dean. The surgeon suddenly looked less pleased. “Too soon to say anything definite. I’ll let you know.” That didn’t sound good. Three days later they put me in a wheelchair and took me to ICU to see Dean. Even before we’d said hello, I could see there was something wrong under the sheets: the bulge where the legs should have been was much too thin. He saw me staring at it. “Yeah,” he said. “The right leg, up near the hip. First night. They did a bunch of X-rays and next thing I knew I was in OR. They said there was no chance and the quicker they got it off the better. They let me keep the X-ray.” He pointed to a slide taped to the wall. Even without any back lighting it was pretty clear. I don’t know if pulverized is a medical term but that’s what I was looking at. The bones inside the leg were broken in maybe two dozen places; the pieces were like small bits of plaster jumbled inside the sack of his skin. “Shit,” I said. After a while: “So, how are you feeling?” “Like any one-legged cliff rat.” But he was still smiling. “At least you’ve still got one good leg,” I joked. His smile disappeared and he pulled the sheet back to expose his remaining leg. The tibia was bent at a twenty-degree angle and the leg was swollen with colors that ranged from black and blue to green and yellow. “A bit of gangrene,” he said. Then, “How about you? Looks like you’re ready to go home.” “Pins in my ankle and a plate in my hip,” I said. “Quite a bit of rehab before they let me go anywhere.” “Great. They want me to start some rehab too, as soon as this leg settles a bit. They say the gym in OT is pretty decent.” The physio wheeled me into Occupational Therapy next morning, and the long painful process began. She helped me out of the wheelchair and draped my arms over the support rails of the walking machine. She started it up, dead slow, and I felt every small step deep in my hip. I stumbled several times before falling onto the moving tread. She looked disgusted, as though I was deliberately sabotaging her efforts, and maybe she was right. They wheeled Dean in a few days later and rolled him up to the hand cycle. “Go as hard as you can,” his physio said, and walked away. And Dean did. The humidity in the Territory is oppressive during the Wet; sweat was soon dripping from his face and arms, soaking his hospital gown. He paused to turn the cycle’s resistance knob up to high before pedaling even faster, and I was pretty sure that he was not just cycling but lashing out at the truckie he had never seen that night, and at the surgeon who had decided that his right leg had to go, and maybe even at me for hitting the brakes at just the wrong moment. Rehabilitate, from the Latin rehabilitare: to restore someone to their original condition. Dean took it to heart. He spent hours in the gym, pumping every bit of iron they had, threatening to wear out the cables on the fixed weight machines. Soon the pecs were back and bigger than ever, and the abs flatter. But not the quads; they weren’t coming back. One day he wheeled his chair under the chin-up bar. I think he’d been eyeing it for a few days. It was set at its normal height, about two meters off the floor. Dean appraised it the way he would a 5.8 cliff face. Then he grabbed one of the supports and hauled himself out of his chair, climbing hand over hand, grimacing whenever his remaining leg bumped against the stanchion. But he kept climbing until he reached the horizontal bar. He grabbed it with one hand and quickly reached the other hand across in a double over-hand grip. He hung there for a moment, evaluating the position. Then he started to rise up slowly. He didn’t bother to swing his remaining leg for momentum as most gymnasts would; he just flexed his biceps and seemed to float weightlessly until he was in the mounted position, his hips resting on the bar. “Hey, ease up, Deano,” I called to him. “Nah, not a problem,” he said from his perch. “After all I’m only lifting half as much weight now.” And he swung his single leg forward to demonstrate. As he did so, his face panicked. But it was too late. He over-balanced and flipped ass over tits, landing with a thump on the mat. I hobbled over to him as he tried to get up. His face was twisted in a grimace, half-smile, half-agony. “I guess I forgot,” he said. “Less weight, less counter-weight,” He tried to laugh but there was a tear squeezing out of the corner of one eye. I looked down to see his remaining leg bent at a forty-five-degree angle, the ragged bone of the tibia jutting like a dagger through the skin.

“Hey, what’s up?” I asked. “These,” he said with a broad grin, and held up his old climbing shoes. “Give me a hand.” He lowered himself to the ground and I helped him put the shoes on his artificial feet. He stood up, stripped to the waist, and clipped a chalk bag to the belt of his shorts. “Deano, seriously?” “I’ve got to try it, Trev. Otherwise I’ve got nothing but a lifetime of writing papers and watching sunsets.” “C’mon, we’re out in the bush, camping under the stars. Just like the old days.” “Stop kidding yourself. This is nothing like the old days,” he said. “You’re nothing like the old days,” he added. That hurt. He was right, but it still hurt. “I’ll belay you,” I said and fumbled in the car for the rope and carabiners that I was sure Dean had stashed somewhere. There was a sturdy-looking bloodwood tree growing out of the cliff face, about four meters up. I managed to toss a rope around it and Dean tied himself off. We’d climbed this cliff many times. But Dean stood back and examined the rock-face as if he was seeing it for the first time. Then he raised his left hand and placed the whole fist into a fissure. His right hand found a finger-grip on a small outcrop a bit higher up. He nodded to me and I tightened the belay line. He bent his left leg and positioned its artificial foot into a small crack. Then he tried to swing his right leg, the one with the full-length prosthesis, onto a foot hold at waist level. But there was no way he could maneuver it with only his hips. He finally simply lifted the prosthetic leg onto the ledge with his right hand. It looked like he now had all four limbs in position, but I could see his right leg wasn’t contributing anything to the effort. I think he knew it too, but he wasn’t giving up. He set his hands onto holds on the next level and lifted his left leg, the one which still had his quad muscles, into another foothold. Then he looked at the next small ledge for the right leg, a meter above the previous one. A simple weight transfer that he’d normally do in his sleep. But Dean knew there was no way the right leg would lift to the next ledge on its own. Rather than use his hand again, he started rocking his body back and forth, letting the right leg swing freely from the hip joint until the heel finally settled on the ledge like a grappling iron. He smiled. But then he put some weight onto the right leg, and I saw it simply slide off the ledge and dangle uselessly in the air beneath him. Dean swore. He began to push with his arms and his left leg, rocking back and forth, building even more momentum. I realized he was going to try a jump. “Deano, no!” He leapt, releasing both hands and his left leg, all his points of contact. He grabbed two finger holds and tried to bring his left leg up into the crack vacated by his left hand. He almost made it, but his right prosthesis was a dead weight. He hung for a moment by his fingertips, then slipped and began to fall. I grabbed the belay rope as it ran out between my hands, burning a raw patch in my palms. I cursed myself for not remembering to put on gloves. I tightened my grip and let the rope slide out slowly until Dean was settled on the ground. I hobbled over to him, but he was clearly okay. He looked at the cliff face. “Again,” he said. He must have tried twenty different routes. Each time he would make it one, maybe two levels up. But his right leg was totally useless, and even a climber of Dean’s ability sometimes needs more than three points of contact. In the end he un-did the right leg’s buckle and simply took it off. That helped, but on each climb he would try a transfer or a jump where three limbs were simply not enough, and he’d end up swinging at the end of the belay rope while I lowered him back to the ground. After an hour his fingers-tips were bloody and my hands were raw from the friction of the rope. He sat down after the last attempt and put his face in his hands. I realized I had never seen him defeated before. It was not something I ever wanted to see again. Finally, he stood up and looked at me. “You want to try it, Trev? You’ve still got all four limbs.” “My hip’s a bit sore,” I said. “Maybe next time”. He said nothing, just strapped his right leg on and walked away. I had followed his routes up the same cliff numerous times. But there was no way I was going to climb it now and upstage him. Dean led, I followed. That’s the way it had always been. I’m sure he would have been strong enough to take it if I succeeded, but I’m not sure I could have. We kept going out, trapping toads, camping, even joking occasionally. But it wasn’t the same. Maybe we were each still trying to figure out what we could do with our diminished selves. For myself, the pleasure I took in life, always small and fragile compared to Dean’s, even that started to slip away, and I strongly suspected it might never return.

I’ve witnessed it a number of times: a wading bird ventures into the shallows at the edge of a billabong during the dry season, foraging intently, head down among the reeds and water lilies. Suddenly a croc will explode from just below the water line, its tail thrashing as it lunges. The bird flaps its huge wings frantically. But a brolga’s wings are made for gliding, not for a quick take-off. Sometimes the bird will escape, able to leap before the croc’s jaws close with an audible snap. Other times the croc will get a piece of it— a wing or thigh or maybe the neck. The bird will struggle wildly for a moment until the croc completes its death roll, and the water closes over both of them. But very occasionally nature throws up a dead heat; the bird leaps at the same instant as the jaws snap, catching not a wing or the body and not the empty air, but a leg. And if the bird is lucky and the croc’s teeth are sharp enough, the bite will sever the thin fragile leg cleanly, cutting through the bone and tendon. And the bird, minus one leg, will escape into the safety of the sky. That must have happened to the lead bird in this mob. Even though the light was fading, it was clear that it was missing one of its legs. “Lost a leg somewhere,” I said. “It happens.” “Not one leg,” Dean shouted. “The second leg! It was shorter as well. Didn’t you see it?” I pointed the binoculars into the dying light. Dean must have had a good look just as the flock was passing in front of the moon. Now they were well away to the north. I focused on the lead bird. Were both legs shorter? Maybe. I couldn’t honestly tell. “Sorry, it’s too dark. I can’t be sure.” “Amazing,” Dean said in a dream-like voice. “Did you see how it was leading the group, hardly flapping at all? Just gliding.” I thought the lead bird was flapping as much as any of the others but said nothing. We drove back to Darwin next morning. Dean stared out the window most of the way, looking at the sky.

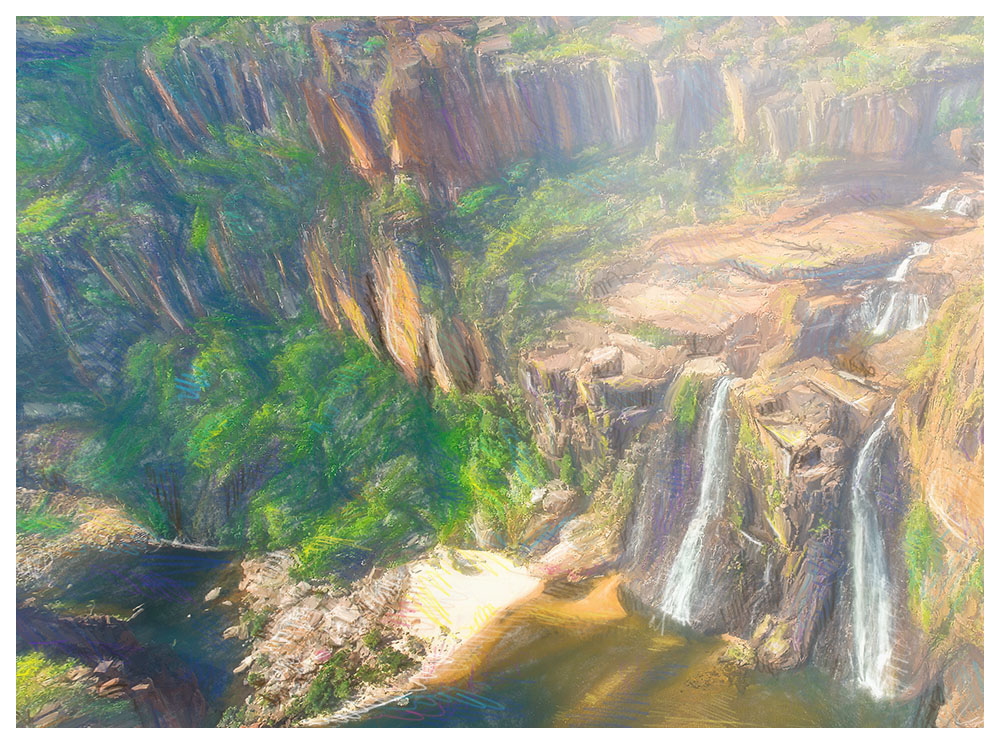

He slipped the suit over his new “legs” and stood up, balancing himself against me as he pushed his arms into the sleeves and zipped it up the front. He checked the fit and stretched out his arms to make the side-wings taut. Then he spread the titanium legs, tightening the secondary wing between them. “There should be a chute in the bag,” he said. “Just in case.” His left leg still bent at the knee, but he had to swing the right leg in a wide arc with each step. He shuffled to the edge of the escarpment and looked down. The falls were just a trickle in the dry season, with a small plunge pool about twenty meters below us. “Do you mind packing up, Trev? If I get high enough, I’ll use the chute. Otherwise I’ll have to splashdown in the pool.” I didn’t try to talk him out of it; no point in that. He stood studying the jump clinically while I gathered up his “street legs” and drove as fast as I could down the loop track. Gunlom is one of the smaller falls in Kakadu but the pool was still a hectare or more. And it’s one of the few without any crocs; Dean had chosen his spot well. I climbed out of the Rover and waved up at him. He spread his wings in acknowledgement and started to hobble forward on his stilt legs, building up a surprising amount of speed. He reached the edge and spread-eagled himself, arms and legs both stretched out wide and hopeful. At first, he struggled to keep his legs apart and simply fell. Then a slight updraft from the warm cliff face caught him and he began to circle, but still falling, spiraling towards the water. He landed on his belly about fifty meters out. He came up spluttering and tried to swim with an awkward butterfly stroke. I swam out and put a forearm under his chin, surf-rescue style. When I could feel the bottom, we tried wading back to shore but the suit resisted every step. I finally picked him up in a fireman’s lift and carried him out. For the first time I realized just how light he was without his legs. We fell together onto the sand, gasping. After a few moments, Dean stood up and raised his head towards the sky. He spread his wings in the warm sun, looking for all the world like a shag drying itself on a rock. When he had dried off a bit, he waddled over to a nearby gidgee bush. “I know what’s wrong,” he announced. “Couldn’t keep my legs apart.” He broke one of the branches, sized it up, and broke a smaller piece off the end. He flopped onto the sand and measured the stick against the space between his “legs”. He looked satisfied and struggled back to his feet. “Again,” he said and marched to the car, carrying the stick. Back at the top he wedged the stick between his legs and said, “Okay, get going!” and stood waiting impatiently near the cliff while I drove back down the track. He couldn’t take a running leap with the stick between his legs, but it wasn’t really necessary. Instead Dean just fell forward, arms and legs spread wide. He caught the updraft almost immediately. He spiraled up to about a hundred meters and circled out over the scrub before turning towards the pool and doing another belly flop into the water. He came up laughing. “All a question of weight,” he shouted as I swam out to rescue him. Gunlom became our favorite destination that season. We made up some cover story about mutating toads, but we were the experts and no one questioned us. Dean practiced constantly— a dozen flights each afternoon. He never did need the chute. Instead he perfected the Deano Drop: an elegant pirouette from horizontal to vertical that slowed his air speed almost to a stop. He was soon landing on his “feet” at the edge of the water and eventually back on the escarpment, arms outstretched like a gymnast sticking a dismount. It saved a lot of trips up and down that bloody track. “You know you’re not supposed to be able to do that?” I said. “No one’s ever landed in a wingsuit,” “It’s all a question of weight,” Dean said with cheeky smile. “What are you working on?” I asked one day. Dean had started keeping a journal, writing it up in the car while I drove home. I tried to sneak a peek but whenever I did, he would lean further towards his window. I got the message. But I couldn’t help noticing the new excitement in him, not just from the flying but from whatever he was seeing up there. June 20th: Able to stick the landings almost anywhere now. Still trying to gain a bit more height. But even at a few hundred meters, there’s a lot more insect life than I expected. Diptera at the lower altitudes but marsh and crane flies up higher. I’m no expert but they seem to be smaller than the ones at ground level. Maybe a new species! About time we branched out from toads. I even thought I saw some kind of wasp hunting the flies. Probably one of the solitary species. Parasitic. We rigged a collapsible trap that Dean was able to carry at the end of his arm. At the speeds he was going, he was able to scoop up just about anything before it could take evasive maneuvers. July 23rd: So many different species of insect! Another surprise: I even caught several spiders. Looks like they’d “flown” up over a thousand meters using their filaments to catch the wind. If there is a food source anywhere, Nature will find a way to harvest it. I broke 5000 meters today. Great view over the coastal swamps and out to Van Diemen Gulf. There is even more life up there than lower down. The helmet-cam caught some great vision of the bird life up there. They seem to be swooping in huge circles, just gliding with their mouths open. Hard to believe that no one has looked for life up there before.

I remember that trip pretty well. Dean’s video of the chicks being fed was amazing. “We’ve got to publish!” I said. “There’s a whole ecology up there.” “We need a lot more data,” Dean said. “And maybe some real proof. The internet’s full of fake videos these days. We might even have to catch one of those scoop-herons before anyone will believe us.” He left the thought hanging. Catching toads for research was one thing. Capturing one of the scoop-herons, when we had no idea how many there were or if we could do it without injuring the bird, was altogether different. I realize now that he had edited the video that day before letting me see it. He never did show me the other “bird” that he had seen. “Are you sure you want to do this?” I asked. We were back at Gunlom. Dean had the wing suit on, with an additional strut fitted across his shoulders that could support his wings, freeing his arms. He’d also added a couple of strategic flaps around the suit’s mid-section, front and back. “Look, it’s the only way to demonstrate that a closed ecology up there is possible.” “But overnight, Dean?” “Yeah, overnight.” And with that he fell off the cliff and rose into the sky. Aug 17th: I spent my first night in the air. I didn’t feel like arguing with Trev any longer yesterday, so I just took off. I wasn’t one hundred percent sure that it would work but there was only one way to find out. I suppose I’ve broken every record in the flier’s book, if I wanted to claim them. Just a question of weight. The suit modifications worked as planned. Thirst wasn’t a problem; there is enough water vapor in the air. And with my hands free I could use the new funnel to feed on insects too. They make great bush tucker. Like witchitty grubs, nutritious and actually tasty once you get used to the crunch. After a while I put the scoop away and just flew with my mouth open. The trick is to position the tongue so that they don’t go straight down the windpipe. I was doing a slow circuit over Melville Island when it started to get dark. I wasn’t sure how I was going to sleep but the shoulder strut made that almost too easy. I only woke up intermittently when I heard the wind whistling louder in my ears and felt myself starting to spiral downwards. But I was always high enough to make a quick correction. After a while my body learned to tense and hold its flight position even as I slept, circling at 3000 meters. The moon came up around midnight, and I can’t describe the view— the rivers and the sea glistened and stars pierced the night sky; there was no sound but the wind. I saw the double-winged “bird” again around dawn. But it’s not a bird. I’m pretty certain it’s human. Tiny, almost child-like, but human. And I swear the face is female. She came closer this time, still cautious but close enough that I could see that the wings were actually some kind of box kite strapped to her back. She moved slowly compared to my wing suit, more floating than flying. We circled each other tentatively. Finally, I yelled out, “Hello! Who are you?” But she just kept circling, watching me from a safe distance, uncertain whether to say anything. Just as I was giving up hope, she flew closer for a moment and I heard her say, “Nama saya adalah Meilin.” Indonesian: “My name is Meilin.” “Nama saya adalah Dean,” I called out. But as I tried to close the distance between us, she simply rose straight up, her box kite gaining altitude much faster than I could follow. I kept circling, looking up at her tiny figure dwindling into the morning sky. She was almost invisible when I heard her shout: “Ikut saya”. But I didn’t understand the words and could only watch as she disappeared into the clouds. I spiraled up to search in the clouds. The damp air hit me like a slap in the face, and the visibility dropped to zero. I called out to her and I had the feeling that she was very close. But she didn’t reply. I circled for hours, flying blind, before finally giving up. I checked the time and realized that Trev would be wondering where I was. With one last look around, I dropped out of the clouds and followed the South Alligator back to camp. In the car, I checked my notepad’s translator. “Ikut saya,” she had said. “Join me.”

“I’ve been injured,” I said and showed her my titanium legs. “I fly because it is the only way I can be free,” I said. That’s when she finally did smile. Between my broken Indonesian, her schoolgirl English, and much help from the translator, I managed to learn her story. She was from the town of Tepa on Pulau Babar, a small Indonesian island north of Darwin. She was ethnic Chinese, and her family was being persecuted in a resurgence of the racism that occasionally swept Indonesia. She said she was sixteen years old, which surprised me until she explained that she was a midget, perfectly formed but tinier than any of her school mates. Because of her ethnic background and her size, she was doubly harassed and bullied at school. Her only solace was flying a kite that her father had given her. She lived not far from the sea and flew it for hours in the strong ocean winds. She began to build her own kites, bigger and sturdier. And one windy day, quite by accident, she was lifted off the ground by one of her constructions. She flew a short distance before falling into the sea. But instead of being frightened, she was exhilarated. She built more kites: kites that would lift her slight body effortlessly, kites that she could strap to herself and control. And she practiced, learning to stay in the air for hours at a time. On the ground she experienced nothing by ridicule; in the air she was free. After one very bad day at school, she left a note for her parents and walked to the rocky outcrop near her home. She strapped her best kite to her back and caught the wind. She never returned. We flew that whole day and into the night. She pointed out a new type of bird, a raptor that preyed on the scoop-herons, and she took me into the clouds to show me where the scoop-herons hid from the raptors. After a while we both slept, she floating and I gliding, and we woke up to discover that we had drifted several kilometers apart during the night. We came back together and laughed. Later in the day, I said, “I must go now. My friend is waiting for me.” “You have a friend?” she said, and her voice was suddenly sad. “Yes, I do,” I said. “At least, I once did.” I started to spiral down. Meilin tried to follow me for a time but the box kite made it more difficult for her to lose altitude than to gain it. When she was almost out of sight, I heard her calling again. “Dean, ikut saya!” Dean wrote in his journal for a long time that evening on the drive back. Then he closed it and just looked out the window at the sky. “What’s up?” I finally asked. “Do you want to join me sometime?” “You mean up there, flying?” “Yeah. Together. We used to do everything together.” “Haven’t you forgotten something? I’ve still got my legs. I’d never get off the ground.” “So, have them removed.” I looked at him and started to laugh. “Hey, c’mon, get serious.” “I am serious, Trev. Why walk when you can fly?” I had no answer to that. We drove the rest of the way in silence. The following week, Dean insisted that we go out again, back to Gunlom Falls. “How long are you going up for this time?” I asked. “No idea,” he said. “But don’t wait up.” And with that he jumped into the air and began a slow spiral into the waiting clouds. I hung around for three days, checking the sky constantly. Then I drove back to Darwin by myself and reported Dean missing. The police asked lots of questions and I explained about Dean’s flying. At first, they didn’t believe me, but I had the videos from his previous flights. There was a search, on land and from the air. Of course, they found nothing— they were looking down. About a month later the head of the department called me in and gave me the spare keys to Dean’s desk. Could I please organize his papers? It would be a fitting legacy if we could publish something posthumously. Dean hadn’t taken his journal on his last trip and I suppose I should have guessed then what he had planned. I found it in his top drawer and started reading. A lot of hints became facts, a lot of suspicions became reality. He had fully documented the aero-ecology, as he termed it: the microbes and insects, with drawings of the bird life, including their diets, their mating habits, their child-rearing. But I knew all that already. What I didn’t know was the story of Meilin. The data was almost ready for publication; I would just have to clean it up a bit and submit it. But the first thing that any reviewer would say was “Where is the proof?” And the race would be on. Soon a dozen universities would have planes and drones in the air over Kakadu, scooping up samples, looking for corroborating evidence. And in time they would find the one thing that Dean would not want found, the reason that he himself had never published anything. Almost inevitably, someone would find Meilin. I had no doubt they were both up there somewhere, despite the official verdict of Death by Misadventure. Dean had made it clear that he could stay up there indefinitely, and Meilin was an even stronger flyer than he was. Perhaps over the years they did land occasionally, stalling gracefully to alight at the top of an escarpment for a drink in the dry season, or to seek refuge in the heaviest storms of the Wet. But somehow, I don’t think they would have stayed on the ground for very long. After all, why walk when you can fly? |

Learn more about Flight of the Brolga by reading the "Behind the Scenes" Author's Notes in DreamForge Anvil Issue 2. Anvil subscribers can also see the actual line edits as Henry worked to edit the story.

|