|

|

“I’d say that was impossible,” I responded, but immediately knew I didn’t believe my own words. At a gut level, what Gabe said felt right.

Gabe must have seen my uncertainty, because he replied to my thought, not my words. “We all know it’s true, don’t we? Places with which we have strong associations feel deeper, richer, more substantial. Even though we can’t see this other world, we can feel it.”

I chewed on my lower lip, considering. “Is this like the ‘vibes’ people talk about feeling at a murder scene or something?”

“Something,” Gabe agreed. ““A lot of those claims are just people letting themselves get over-stimulated by the idea that something significant happened at a given location. This is the real thing. It’s true that strong emotions are more often associated with something bad, rather than with something good. That’s why a single negative event can overshadow a lifetime of positive associations.”

“I don’t get what you mean.”

“Here’s an example… A newlywed and her husband build a home. They live there. Raise a bunch of kids. Celebrate all sorts of great things. Then one day he has a heart attack in the family room and dies in his favorite chair. The widow insists on moving, says she feels haunted.”

“And?”

“She is, but not by her late husband. She’s haunted by her own shock and horror at finding him dead, by the ruination of all her dreams regarding their future together. That’s what she can’t escape.”

“I follow you…” I considered. “The memory I’ve lost… It isn’t negative. I mean, I don’t think it’s negative. I hope it isn’t. That’s why I’m so stressed. Until I know…”

“Not all the memory structures are negative,” Gabe said. “Some of the most powerful structures are created by experiences so intense you can’t really remember them afterwards. The emotions pour into you and overflow.”

“If that’s how it works,” I protested, “some scrap of the memory should remain. I can’t remember anything.”

“You’re thinking of this ‘overflowing’ as if you’re a pool or basin. Actually, you’re more like a channel. Imagine these intense emotions as a gully washer that comes sweeping through, carrying everything in front of it and leaving nothing behind.”

“All right. But you said that there’s a landscape built from memories. How does that happen if the memories are washed away?”

“They’re washed from you,” Gabe said with angelic patience. “I didn’t say they were washed from there. They’re washed to there, copied or imprinted on the landscape. Pick whatever terms you’re happy with. What’s important is that, if you move quickly, you should be able to find the missing memory.”

“Should?”

“That’s right. Structures born from memory are chancy. Some last for a long time. These are usually associated with the sort of places that are constantly recharged with strong emotions.”

“Funeral parlors,” I suggested. “Hospitals. Airports.”

“Churches,” Gabe added. “Sports arenas. Schools. They’re disproportionately intense. A home or even an apartment building is going to be smaller, harder to find. You’ll need a guide.”

“You? I wouldn’t want to inconvenience you. Anyhow, I should be able to find the place pretty easily. I know exactly where I want to go.”

“I doubt you’d be able to navigate the landscape as easily as you think,” Gabe replied. “The landscape’s not just made of your memories. It’s made of all the memories associated with a given location. Good memories, bad memories, happy memories, bittersweet…they’re all there, layered on each other like…”

He paused, searching for a metaphor.

“Like an onion?” I suggested.

“I was thinking of one of those fancy desserts, like a baklava or a napoleon. Or one of those cakes with at least fourteen layers and cream in between.”

“Mmmm…”

“Give it up,” Gabe urged. “Try to move forward. There could be pastry in your future yet.”

I shook my head. “I can’t. I’ve tried, but I can’t.”

“If you insist, then I’ll introduce you to a dragon who might help you.”

“Did you say ‘dragon’?”

“I did.” Gabe sighed and tousled his hair again. At least he wasn’t pulling it out at the roots. “Dragons hunt where dreams collect. They burrow in the rubble, swallow what they find there.”

“Did you say ‘swallow’?”

“I did. Dragons eat accumulated emotions. We’re lucky that they do. Otherwise, the bleed-through would drive crazy anybody with the least bit of sensitivity. That’s why even a place freighted with emotional significance eventually goes back to neutral.”

“I guess that makes sense,” I said, thinking of tours I’d taken to historically significant places, how they’d seemed sort of vanilla. I’d always credited that to my lack of sensitivity – which is a pretty odd thing for an artist, especially one who had more than her share of what is often termed “artistic temperament.”

Gabe was still explaining. “Dragons savor their finds as an oenophile savors a rare vintage – and like the oenophile, they destroy what they most treasure.”

“That doesn’t sound good.”

“It isn’t, at least for you – not if that memory is as crucial to your peace of mind as it seems to be.”

“It is. If I can’t find out what happened, I’ll go crazy. It’s important.”

“Lydia, I know I’m the one who brought this up, but there’s a reason I don’t want you to try this. Humans are nothing more than dense bundles of memories. I’ll ask Arcadia not to eat you and he won’t, but…”

“There might be other dragons and they might not be as restrained?”

“There will be other dragons and, as soon as they get your scent, they’re going to come looking for dessert.”

“Oh…” I shrugged. “What do I have to lose?”

“A lot. You’re worried about the absence of one memory. If you’re not careful, you’re going to lose them all.”

|

The dragon Gabe summoned to be my guide was called Arcadia.

“Isn’t Arcadia a place?” I said. “Like in Shakespeare, a sort of rural paradise?”

“Yeah,” Gabe laughed. “Arcadia is a specialist in dreams of rural bliss. You might say he’s eaten more dreams of Arcady than anyone else.”

Arcadia reminded me of a lizard or dinosaur rather than a dragon. My mental image of dragons includes wings. Arcadia didn’t have any. My personal opinion was that a dragon should be more flashy – metallic scales in hues of gold or silver or flame, perhaps. Arcadia was a mottled dull brown that would blend in perfectly against rock or desert.

I wondered if Arcadia craved those dreams of rural paradise precisely because he was so dully colored. Maybe he felt more beautiful when rich greens and floral bowers flashed through his system.

Yet, despite his muted coloration, Arcadia was beautiful in his non-classical dragon fashion. His head was almost deer-like, with large, liquid eyes that shifted from light to dark brown depending on his surroundings. Where a deer’s ears would be, he had two curving horns that pointed forward. His torso – he didn’t really have a separate neck – was crested with spikes that extended down to its base. His tail resembled a gradually tapering boa constrictor. His three-clawed hind feet were enormous, enabling him to balance upright briefly, although not to walk bipedally. His front feet were much smaller, the taloned digits positioned so he could use them like hands with two thumbs and three long extra-long fingers.

After introductions were completed, Gabe invited Arcadia to sniff me all over. The dragon did so, then sneezed.

“Arcadia will use your scent to take you directly to the cognate of the area where you lived most recently. He’ll also take you to the right location. After that…”

“It’s up to me?”

Gabe nodded, then turned to Arcadia. “Ready?”

| The dragon Gabe summoned to be my guide was called Arcadia.

“Isn’t Arcadia a place?” I said. “Like in Shakespeare, a sort of rural paradise?”

“Yeah,” Gabe laughed. “Arcadia is a specialist in dreams of rural bliss. You might say he’s eaten more dreams of Arcady than anyone else.”

|

The dragon nodded, a sort of pushup motion that involved the entire front of his body. He stared at the space directly in front of him, his eyes darkening almost to black. His nostrils flared. The spikes along his torso raised vertically, making me glad I hadn’t suggested I ride on his back – something I had thought about, so we wouldn’t get separated.

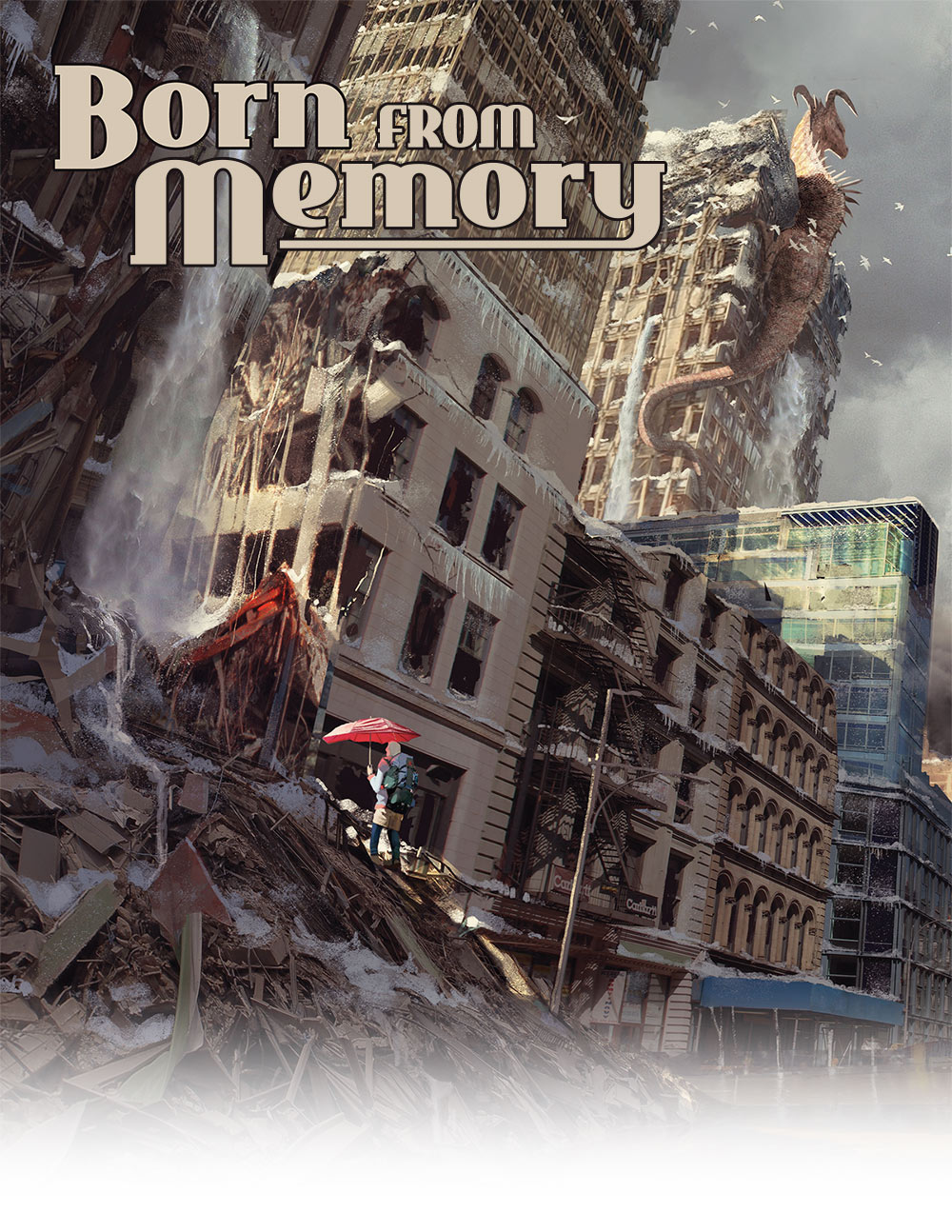

The air in front of Arcadia wavered, the way it does over a hot electric burner. Then it began to peel back, revealing a barren cityscape that looked as if it had been ravaged by an earthquake. Cold air wafted out. Shivering, I realized that icicles dripped from the rubble. There was spray in the air that stung like sleet.

“It’s cold!” I gasped.

Arcadia chuckled. “Thou hast heard the phrase ‘frozen in memory’? There is truth to it.”

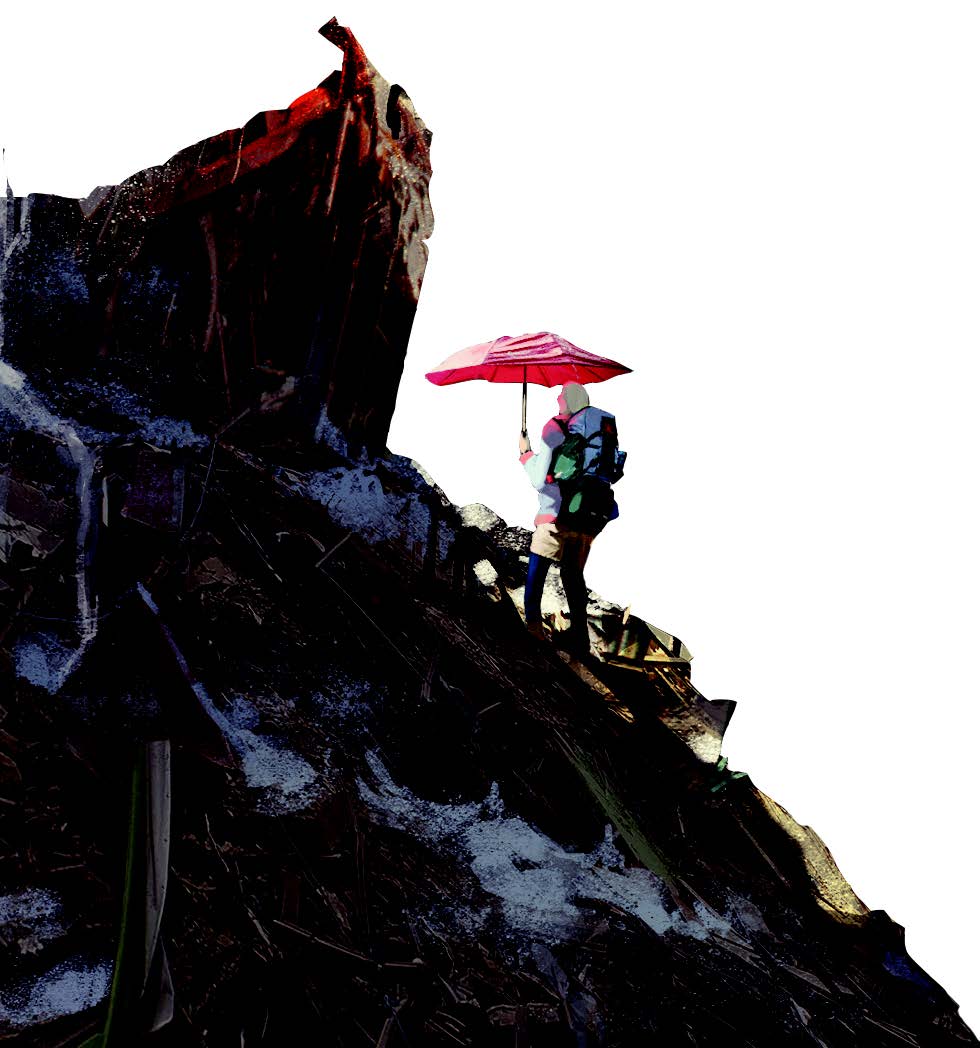

Gabe handed me a heavy coat and hat. I was already dressed for hiking. Then he helped me set a large pack upon my shoulders. Lastly, he thrust a furled umbrella into my hand. I wondered why I’d need so much gear just to find a memory but, looking through the opening Arcadia had created, I understood. In this destroyed landscape, going even a few blocks would be tough.

“I had no idea it would be so…so ruined!” I said, looking around the dragon’s smooth brown flank and through the opening.

“My brethren, my rivals,” came Arcadia’s dry, rasping voice. “My sisters, my people. They have been hunting here. Thus the damage.”

He lifted his head and the curved horns moved, questing like antennae. “The others are not nearby at this moment, but they may be close enough to scent you, little seeker. Dost thou still wish to go forth?”

“More than ever,” I replied as stoutly as I could. “Gabe warned me that memories do not last forever, even here.”

“Less long,” Arcadia agreed, “when my people are about. I shalt not be able to attend upon thee as closely as we had hoped. I must go where I can scout out – perchance distract – those who will surely catch your scent. Are you ready?”

“Let’s go!” Pausing only to give Gabe’s hand a firm shake, I stepped forth. Arcadia trundled alongside, standing a little over me. His underbelly was lighter than his upper, patterned like light on water.

Our first steps splashed us into what looked like a river framed by half-ruined buildings. The surface underfoot was slick, part water, part ice, so that with each step I slid, crunched, and splashed. Arcadia, with his clawed feet, did better than I, but the heavy, ankle-high hiking boots Gabe had insisted I wear kept my feet dry and gave as good footing as could be hoped for. After several steps, I realized we were standing in the middle of what had been a roadway, although there were no vehicles anywhere in sight.

“I almost know this place,” I said, craning my neck to look up and around. “That building in front of us, the one with the blue awning. It reminds me of the Grande Hotel. The one next to it, though… The one with the old-style fire escapes. I don’t know it.”

“It was a department store,” Arcadia replied. “Torn down some five years ago. It still features in people’s memories so, for now, it remains.”

“I think I remember hearing about that store,” I mused. “People were divided as to whether its removal was urban beautification or loss of a landmark. Looking at it now…”

“A place here does not always look as it does in the present world,” Arcadia reminded me. “Memories overlap. A memory from one season conflicts with that of another. If they are strong enough, memories may distort the size, even the shape of a structure. Look there, down beyond the hotel. Do you see the green building?”

“I do. Don’t know… Wait! That’s the hospital, isn’t it? I wouldn’t have known it if I hadn’t spent so much time there. The features seem to shift, as if we’re somehow seeing all sides of it at once.”

“The hospital, yes,” Arcadia agreed. “Shaped by so many memories that one image could not hope to contain it. Beyond it, do you see the tall building with water gushing forth?”

“I do. It’s not in very good shape, is it?”

“No. Dragons have been there, and recently. Flowing water shows that. When we devour memories, water flows, carrying the detritus away. Sometimes new memories rebuild a place. Sometimes, not. I shall climb aloft to see if I can discover where the dragons have gone. Do you recognize enough to direct your own search?”

I looked side to side and was about to say “No, I don’t,” when, with a sinking feeling in my gut, I realized what I was looking at.

“Oh, dear god…” I managed, my voice so tight and strained I hardly knew it. “You brought us very close. Do you see that heap of rubble, down from where the department store was? That’s my old apartment building!”

“That is where you need go then,” the dragon said, turning away.

“But there’s nothing there!”

“How wilt thou know,” Arcadia asked, “unless thou lookest?”

I had the feeling I’d disappointed the dragon by turning coward. After all, I was the one who had insisted on coming here.

“You’re right. Be careful, now.”

Arcadia’s horns curled tight in what I realized was the equivalent of laughter. “I shall. From my memories, I will draw white doves if need arises to send thee a message. Go now. Balance swiftness with caution. Perhaps all is not lost.”

He swiveled his long torso, splashing away along the water and ice filled channel that had once been a busy street. I shook my head, hard. Somewhere it still was a busy street. This place was memory and distortion – not reality.

I began climbing the slippery, ice-crusted mound of rubble that had once been my home. As I struggled, several times sliding back almost to the street, I remembered how I had come here.

Three years earlier, I had been diagnosed with a rare cancer. That was the bad news. The worse news was that what I had was so rare there wasn’t even a treatment protocol. The worst news was that they gave me about two years.

Then the good news came. The daughter of a really rich man – some sort of software entertainment magnate – had been diagnosed with the same cancer. No fundraisers for Mr. Bucks, no banquets with thousand dollar tickets. He just started throwing money toward finding a solution. Problem. The researchers needed test subjects. Like I said, the cancer was very rare. They found me. I was offered a job as guinea pig.

I took it. On odd days, I hoped they’d actually find a cure. On even days, I settled for believing I was doing something useful. Maybe they would find a cure for me and Melody and the rest. Maybe they’d be too late for me, but they’d learn enough to save someone else.

I’m not going into details about those years. If there were memories I would choose to forget, those would be the ones. I hadn’t liked needles before. Within a few months, I liked them even less. Wait… I said I wasn’t going there and I’m not, not except for the part that matters…

Mr. Bucks was really good to me and the other guinea pigs. In most cases, we were all relocated to the same city, so we’d be close to the hospital that was the center of the project. He and his family already lived in the vicinity. The few who couldn’t relocate for one reason or another were flown in on chartered jets.

Our patron offered us a choice of accommodations within easy reach of the hospital. I asked for a place with a studio where I could paint when I felt well enough. To my astonishment, I was given the entire top floor of an apartment building. It was remodeled so that there were several studios, each positioned to take advantage of natural light at different times of day, so I could take advantage of any chance moment. A private elevator was put in. I even had a live-in nurse caretaker.

I did paint when I felt well enough, which wasn’t nearly as often as you’d think. Still, I probably painted more often than I would have if the cancer hadn’t made it possible for me to quit my day job. I mean, I was good. I’d even had some gallery showings, but I wasn’t making a living. I was seriously aware of the irony.

We lost people from the team almost from the start. Mack had been diagnosed too late and was already weak. Cynthia got some rogue infection. Tansy reacted badly – not to the drug being tested, but to an unpredictable synergistic reaction between it and her blood pressure medication. Others, after months of needles and tests and more tests, ups and downs, and, worst of all, the poisonous hope that came after each trial, only to be dashed again, dropped out, preferring to die slowly and peacefully, drugged to the gills in some hospice.

Mr. Bucks may have resented their retreat – but maybe not – maybe it just made him even more grateful to those of us who kept on with the trial. He continued to pay the dropouts’ expenses, just as he’d promised, even though Melody got worse, becoming thinner and weaker, the slender figure that looked so beautiful in the photos I’d seen of her (remember, she was the daughter of a very, very rich man and fair game for the tabloids and fashion magazines) becoming gaunt and ragged.

|

I don’t know what I looked like. I’d asked that the apartment be decorated without mirrors or obviously reflective surfaces. I avoided catching my reflection by chance – one good thing about being an artist was that I could pretty much guess where these would be.

Last time I’d heard, Melody wasn’t doing well. During trials, we’d often been roommates. Lately, I’d heard she was living in a sterile room, protected from any chance of infection. I hoped she was okay. I’d expected her to be a brat, a spoiled child of privilege, but she was one of the rare ones who learned from watching those around her – including, so I guessed, her own mother, a shallow, self-centered creature who made Jenny Churchill look like Mother Teresa.

Melody and I had been on about the same progression curve, so when I heard how poorly she was doing, I decided the time had come for me to complete my final painting. I’d been working on a tribute to all of those in the test group, a project I’d started after Mack had died. I knew the galleries wouldn’t like it. They’d call it “sentimental,” dismiss it for being too photo realistic. I didn’t care. I was long past the days when I had obsessed over my artistic legacy. The closer I drew to closing my eyes that final time, the less legacy seemed to matter.

I’d collected photos from all the members of our test group or from their families. The doctors, too, and the nurses and techs and researchers, for they had done the remarkable. A few, knowing us for the doomed, had withheld their hearts. Most, however, had given us all they had – wept even more readily than we had, celebrated every small victory. I knew that each and every one of them at some time or another had struggled with the belief that they were failing us. We guinea pigs might have put our bodies on the line, but the medical staff had offered their souls. They belonged as well.

Now, as I struggled up the slippery slope, wondering in some corner of my mind if what was keeping me from making forward progress was my own fear at what I might find – or fail to find – I concentrated on the painting. I’d placed us in a setting inspired by Seurat’s “A Sunday Afternoon on the Island of La Grande Jatte.” You might know it as the painting featured in the musical Sunday in the Park with George.

I hadn’t used Seurat’s impressionistic style, though, because I wanted everyone to be perfectly recognizable. I’d spread the figures over several canvases, so that no one need be diminished. If the piece was ever displayed (and I doubted it would be), the canvases could be hung side by side, creating the illusion of being one piece. Once I would have used a huge canvas and a scaffold, but I was beyond such exertions.

Nearly on hands and knees, I made my way closer to the top of the rubble heap. Icy water misting down from above was making bad footing worse. Belatedly remembering the umbrella Gabe had given me, I unfurled it. It was bright red, the color – not of blood, that’s darker, as I knew all too well – but of poppies.

“Fitting,” I said to no one in particular. “Poppies are for remembrance, no matter what Ophelia said about rosemary. There are other battlefields than Flanders.”

A shaft of light pierced the mist, reflecting off the umbrella’s dome and casting a brilliant glow on a heap of rubble in front of and above me. That was my first thought at least.

“No, it can’t be that. The angle isn’t right. What then?”

Poppies, a little voice said in my mind. It sounded like Melody, before she’d gotten so weak that all she could do was whisper. For remembrance.

|

The elevator cage was somewhat crumpled, but I had enough room to open my umbrella. I wedged it so that it caught the sunlight filtering through the rubble, tinting my private universe the same translucent red as the splash of color that had brought me here.

Red Sky at night, I thought, Lydia’s delight. Red sky at morning, dragons take warning!

Closing my eyes, I reached out to where the elevator buttons should be, not permitting myself to think that I hadn’t seen them earlier, when I’d first entered the ruined cage. I’d pressed them so often, often by memory, so then…

I felt them. Smooth, slightly raised, the bumps of Braille alongside. I pushed the button for up and felt the elevator begin to rise. A gentle ping announced the first floor, second floor, third, fourth, then, finally, my own… Only when the elevator stopped and I heard the doors slide open did I move. Eyes still shut, I walked forward, focusing hard on my memory of my apartment as it had been the last time I had seen it.

When Mr. Bucks had the floor remodeled for me, hallways had been eliminated wherever possible to ease the passage of wheelchairs. The elevator opened into a wide foyer that, in turn, opened to the largest room of the apartment. This had been the one I’d been using as my studio toward the end. The finished panels of the tribute painting were hung, unframed, on one of the walls. There was a gap in the middle of the bottom row. That painting should be on the easel near the window…

I forced myself to look, afraid of what I might see. Afraid, more, of what I might not see.

“I had no idea I looked so bad,” I said aloud. My voice sounded strange, like I was in a small, enclosed space, even though to all appearances I was in a large open one. “No idea…”

The figure who sat in the wheelchair in front of the easel didn’t react to my voice. She kept painting, her head alternately craning forward and pulling back, as if finding an acceptable range of vision was difficult. She looked a wreck: skin both slack and bloated, scalp hairless, shoulders hunched. She looked about ninety, although I knew she was barely thirty-six. Only her hands and arms were steady. One held the paintbrush, the other the palette on which paints were arrayed. She was painting with a focused determination that said she knew time was running out.

I found I could move closer. Now, at last, I could see what I had come to learn. The picture on the easel was of two young women. One – prettier by far, wore a pale ivory dress with pink rosebuds and lace at wrist and collar. Her hair – a rich auburn that owed nothing to a bottle – spilled loose over her shoulders, almost to her waist.

She was sitting on a picnic blanket spread beneath a birch, leaning against the tree’s trunk, reading out loud from a book of verse. Her audience was seated in front of an easel, wearing paint-smeared jeans and a well-used smock. There was a resemblance between the painter and the wreck in the wheelchair. They even wore the same smock.

Me. Of course. The other woman was Melody. During the early days of our treatment, when we were weak but not hopeless, she’d promised me that she’d take me to her favorite spot on her parent’s estate.

“You’d love it there. It’s so peaceful. You could paint and I’ll read to you or something.” Her voice had turned wistful. “Think of it. No pinging monitors. No needles. No medicinal smells. Birdsong and the chatter of water over rocks.”

“And the chatter of you,” I’d laughed. Melody loved to talk. She even had things worth listening to, remarkable in a girl of only twenty-two.

We’d never make it there. Not in reality. But that was how I wanted to remember us. Not as we had met – sick, dying, increasingly decrepit – but as we had hoped we would be. Surely the dreams were at least as valuable as reality.

But had I finished? That’s what I needed to know. Like many artists, I had my own sheaf of superstitions. Mine was that, although I roughed them in, I never finished the eyes before the painting was done. It creeped me out to see apparently living eyes peering out of a partially completed canvas – and I’d learned that it made it almost impossible for me to scrape away and restart, because somehow the piece was already alive and it felt like murder.

So had I finished the eyes? Mine were done. They would have been easier, since I was in profile, focused on the canvas, but Melody? Her eyes were a particularly distinctive shade of green, not brilliant emerald or hazel, but akin to one of the darker jades. I’d anguished over getting it right…

The painter me was blending paint, trying a bit, shaking her head with frustration. Not right… not right… And I could feel how tired I was getting. Soon my hands would begin to shake and I could never manage anything as detailed as eyes when they did.

And I knew with the absolute certainly of the dying that I wouldn’t have another chance.

“Lydia?” A voice from the other room. Carrie, the admirable woman who had been my nurse companion. “Shouldn’t you take a break, dear? You’ve been painting for quite a while now. Maybe a little tea?”

“All right,” I called, my voice cracked and hoarse, like something from a horror film. “Oolong?”

I chose oolong because Carrie was a tea snob. We’d been given a very fine blend by Mr. Bucks. I knew she’d make sure the pot was preheated, the water the perfect temperature. It would give me time…

That was the last thing I remembered. What I remembered next was being in the hospital. Apparently, when Carrie had come in with the tea, she’d found me unconscious. I couldn’t make anyone understand what I needed to know. And then, in the night, I’d died.

Please, Lydia, I begged myself. You have maybe five minutes. Don’t waste them. Don’t let Melody be uncompleted. If she’s got to die, let her live at least in memory.

The painter me at last seemed satisfied with her colors. She started laying them on, not quickly – there was no time for quickly, because there was no time for a mistake. Deliberately. Green. Then shading. A rim of slightly darker green around the iris. A pupil – that had to be just right. The whites. Detail on the lids and rims. A touch-up on the lashes.

The painter’s hand fell limp. Brush and palette slid to the floor. Melody stared out of the canvas, as alive as she never would be.

I realized I was weeping, but with happiness, not sorrow. I had my memory back. I hadn’t failed. I might not have beaten the cancer, but I hadn’t failed. The room that had been my studio faded from around me, as my right to memory ended.

|

When I opened eyes I hadn’t realized were shut, I found myself surrounded by dragons.

Humans, as Gabe had said, are little more than bundles of memories. So, it turns out, are dragons. There are differences, of course. Humans make memories. Dragons hoard them. They don’t destroy them – Gabe was wrong about that, but then even angels aren’t perfect.

Dragons take memories into themselves, digest them, remember them, make them into something with scales and tails and, sometimes, even wings.

I have wings. They’re bright as poppies.

And I remember.

|